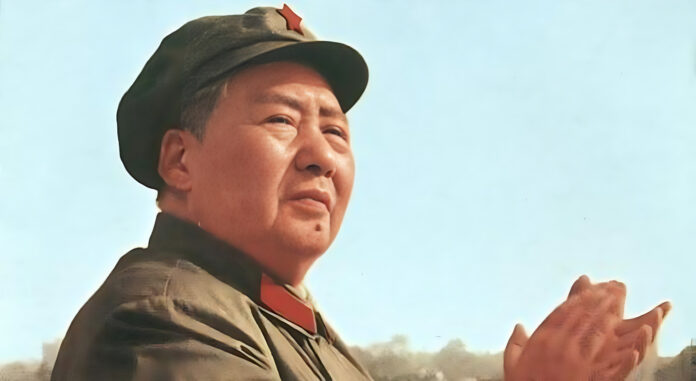

On December 26, 1893, Mao Zedong was born in the small village of Shaoshan, Hunan Province, China. A towering figure in 20th-century history, Mao rose from modest beginnings as the son of a farmer to lead one of the most consequential revolutions in modern history. As the founding father of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), established in 1949, he served as its chairman until his death in 1976, shaping the course of Chinese society and leaving an indelible mark on global geopolitics.

Mao’s early years were steeped in a China in turmoil—dominated by foreign powers, riddled with internal strife, and grappling with the decline of the Qing dynasty. As a young man, Mao developed an interest in Marxist theory while studying at Changsha and later Beijing. His political career began in earnest when he co-founded the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1921. Mao’s strategies diverged from traditional Marxism, emphasizing the mobilization of rural peasants rather than urban proletariat, a shift that would become a hallmark of his revolutionary tactics.

Mao’s leadership was solidified during the Long March (1934–1935), a grueling retreat by communist forces that cemented him as the de facto leader of the CCP. The communists’ eventual victory in the Chinese Civil War against the Nationalists (led by Chiang Kai-shek) culminated in the proclamation of the PRC on October 1, 1949.

Achievements and Controversies

Mao’s tenure as China’s leader was defined by sweeping reforms, some of which had transformative effects, while others led to catastrophic outcomes. Land redistribution and social reforms aimed at equality earned him the support of millions, while his vision for a self-reliant, industrialized China underpinned the Great Leap Forward (1958–1962). However, this ambitious campaign to boost steel production and collectivize agriculture resulted in widespread famine, with millions perishing.

The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), another signature initiative, sought to purge “counter-revolutionary” elements from Chinese society and reassert Mao’s control. While it energized a new generation of young “Red Guards” loyal to Mao, it also led to immense cultural and social upheaval, targeting intellectuals, destroying historical artifacts, and causing widespread persecution.

Legacy

Mao’s death on September 9, 1976, marked the end of an era in China. Though his policies remain contentious—credited with unifying and modernizing China while also blamed for devastating human suffering—his legacy continues to shape Chinese identity and politics. Revered by some as a symbol of resilience and independence, he is criticized by others for the heavy human toll of his policies.

Statues of Mao still stand across China, and his image adorns the country’s currency, a testament to his complex and enduring role in Chinese history. Mao Zedong remains a pivotal figure in the story of modern China, his life a reminder of the profound power of revolutionary ideals—and their potentially far-reaching consequences.