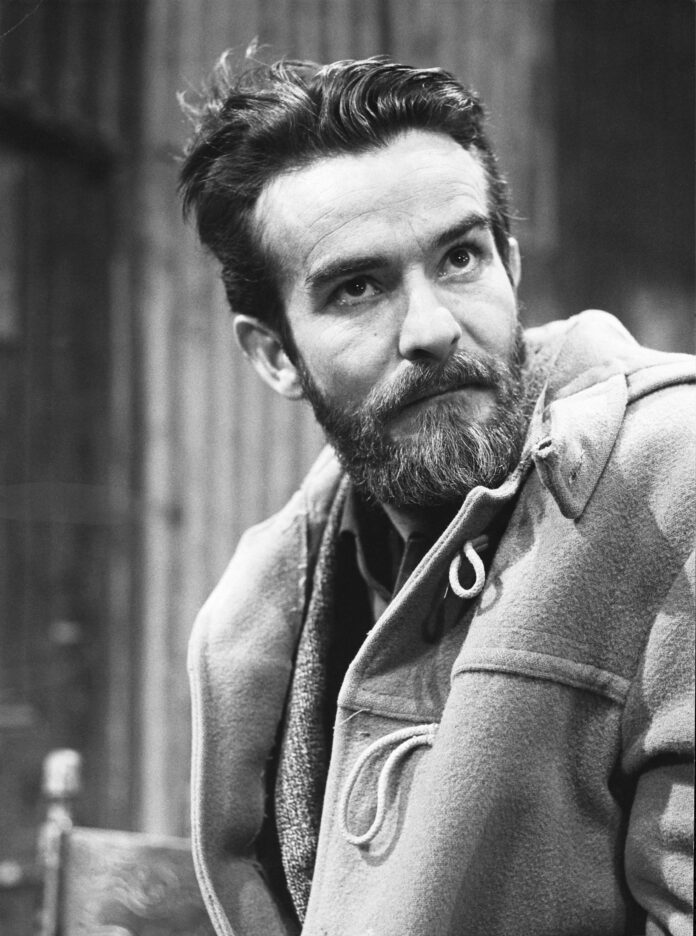

Athol Fugard, the celebrated South African playwright whose searing dramas chronicled the human cost of apartheid and brought international attention to the injustices of his homeland, died on March 8 at his home in Stellenbosch, Western Cape. He was 92.

His death marks the end of a remarkable seven-decade career during which Fugard produced more than 30 plays that earned him recognition as South Africa’s greatest playwright and one of the most significant dramatists of the 20th century.

Born Harold Athol Lanigan Fugard on June 11, 1932, in Middelburg, Eastern Cape, Fugard was the son of an Afrikaner mother who operated a general store and later a lodging house, and a disabled father of Irish, English, and French Huguenot descent who had been a jazz pianist. The family moved to Port Elizabeth in 1935, where Fugard would spend his formative years and which would later feature prominently in his works.

After studying philosophy and social anthropology at the University of Cape Town, Fugard dropped out in 1953, a few months before his final examinations. He spent the next two years working on a steamer ship in East Asia, an experience that later inspired his autobiographical play “The Captain’s Tiger: a memoir for the stage.”

In 1956, Fugard married Sheila Meiring, a drama student, and began organizing multiracial theater productions—a radical act in apartheid South Africa. His early works “No-Good Friday” (1958) and “Nongogo” (1959) featured Fugard performing alongside black South African actor Zakes Mokae.

Fugard’s breakthrough came with “The Blood Knot” (1961, later revised as “Blood Knot” in 1987), in which he and Mokae portrayed brothers of different racial classifications. After the BBC filmed a version of the play in 1967 with Fugard in the cast, the South African government confiscated his passport, a measure of the threat they perceived in his art.

In the 1960s, Fugard formed the Serpent Players, a group of black actors who worked day jobs as teachers, clerks, and industrial workers while developing plays under surveillance by the Security Police. This collaboration led to landmark works including “Sizwe Banzi Is Dead” and “The Island” (both 1972), co-authored with actors John Kani and Winston Ntshona.

His most autobiographical play, “Master Harold”…and the Boys” (1982), dealt with the complex relationship between a white South African teenager and two Black men who work for his family. The play had its world premiere in the United States, performed by Danny Glover, Željko Ivanek, and Zakes Mokae at the Yale Repertory Theatre.

Throughout his career, Fugard refused to stage his works for whites-only audiences, supporting an international boycott of racially segregated South African theaters. This principled stance led to additional restrictions and surveillance by the apartheid regime, compelling him to have his plays published and produced internationally.

Time magazine in 1985 acclaimed him as “the greatest active playwright in the English-speaking world,” and his influence extended far beyond South Africa. Several of his plays were adapted into films, including “Tsotsi,” based on his only novel, which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 2005.

After the end of apartheid, Fugard continued to write plays that explored the complexities of post-apartheid South Africa, beginning with “Valley Song” in 1995. His later works, including “Coming Home” (2009) and “The Train Driver” (2010), examined the challenges and disappointments of the new South Africa with the same unflinching honesty that characterized his earlier work.

Fugard received numerous honors throughout his career, including the Order of Ikhamanga in Silver from the South African government in 2005 for “his excellent contribution and achievements in the theatre.” He was named an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and received a Tony Award for lifetime achievement in 2011. Cape Town honored him with the opening of the Fugard Theatre in District Six in 2010.

Beyond his work as a playwright, Fugard was also an accomplished actor, director, and teacher. He appeared in films including Richard Attenborough’s “Gandhi” (1982) and Roland Joffé’s “The Killing Fields” (1984). For several years, he taught playwriting, acting, and directing at the University of California, San Diego, and served as the Wells Scholar Professor at Indiana University for the 2000-2001 academic year.

After almost 60 years of marriage, Fugard and Sheila divorced in 2015. He married Paula Fourie, a South African writer and academic, the following year. Fugard is survived by Fourie and their two children, daughter Halle and son Lanigan, as well as his daughter Lisa from his first marriage.

Although increasingly critical of post-apartheid politics in South Africa, Fugard returned to his homeland in 2012 after years of living in the United States. In 2006, he had reserved a grave plot for himself in Nieu-Bethesda, a village in the Karoo where he had a home and which inspired his play “The Road to Mecca.” He had expressed the wish to have his gravestone inscribed with the remark of a black child he had once passed while running uphill: “Hou so aan, Oubaas – jy kom eerste!” (“Keep going, boss – you’re coming first!”).

Athol Fugard’s unflinching examination of the human condition under apartheid gave voice to the voiceless and forced audiences worldwide to confront uncomfortable truths. His works, which continue to be performed globally, stand as a testament to the power of art to illuminate injustice and inspire change.

Disclaimer

This obituary is based on verified information about Athol Fugard’s life and career following his death on March 8, 2025. Image Source: Athol Fugard 1970 – Image by Hulton-Deutsch, Courtesy of Face 2 Face Africa.