What Is Carried Interest?

Carried interest is a share of profits that investment managers receive as compensation, typically in private equity firms, venture capital funds, hedge funds, and real estate partnerships. Unlike regular income, it has historically enjoyed preferential tax treatment that allows fund managers to pay lower tax rates than many ordinary workers—a feature that has sparked significant debate about tax fairness in America.

How Carried Interest Works

Most investment funds operate on a “two and twenty” compensation model:

- Two: A 2% annual management fee based on assets under management

- Twenty: A 20% share of profits (the carried interest) if investments exceed a predetermined threshold

For example, in a $100 million fund, managers would receive a $2 million annual fee regardless of performance. If the fund generates $50 million in profits, managers would also receive $10 million in carried interest (20% of profits), but only after returning original capital to investors plus a minimum return (often 8%, known as the “hurdle rate”).

The Tax Advantage

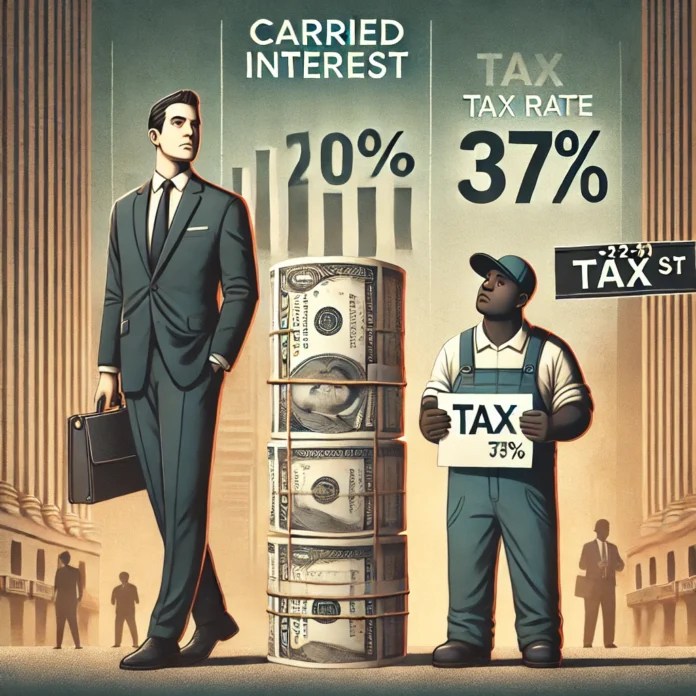

The controversial aspect of carried interest lies in its tax treatment. While the 2% management fee is taxed as ordinary income (currently up to 37% at the federal level), carried interest has historically been taxed as long-term capital gains if the underlying investments were held for more than three years (a rate of just 20% for high earners).

This creates a situation where fund managers earning millions or even billions can pay lower tax rates than many middle-class professionals like teachers, nurses, or firefighters who pay ordinary income tax rates.

The Economic Justification

Defenders of the carried interest tax treatment offer several justifications:

- Risk alignment: Carried interest incentivizes fund managers to maximize returns since they only profit when investors do.

- Capital investment: Some managers argue they’re putting their own capital at risk alongside investors, justifying capital gains treatment. However, critics counter that managers typically invest only a small fraction of total fund capital.

- Entrepreneurial reward: Fund managers view themselves as entrepreneurs building businesses, deserving the same tax treatment as business founders. However, unlike traditional entrepreneurs, fund managers do not personally take on financial risk in the same way, as they primarily manage investor capital rather than their own.

- Economic competitiveness: Advocates suggest higher taxes would reduce investment activity and drive financial talent overseas.

The Arguments for Reform

Critics offer compelling counterarguments:

- Labor, not capital: Fund managers primarily contribute expertise, not capital. Their performance-based compensation is fundamentally payment for services rendered, not a return on investment.

- Horizontal inequity: Similarly compensated professionals (like corporate executives with performance bonuses) pay ordinary income rates.

- Revenue loss: The preferential treatment costs the Treasury billions in lost tax revenue annually. The Joint Committee on Taxation has estimated that closing the loophole could generate roughly $14 billion over a decade.

- Wealth concentration: The tax advantage disproportionately benefits already wealthy individuals, exacerbating income inequality.

Policy History and Recent Developments

The carried interest tax treatment has survived numerous reform attempts:

- 2007: Congress first seriously considered eliminating the loophole.

- 2017: The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act modestly extended the holding period requirement from one to three years.

- 2022: The Inflation Reduction Act initially included provisions to narrow the loophole but ultimately only included minor adjustments.

- 2025: Under President Trump’s administration, the debate over carried interest taxation has resurfaced, with renewed calls for reform as part of broader tax policy discussions.

Recently, the conversation has evolved, with even some investment managers acknowledging that the preferential treatment may be difficult to justify. States like New York have considered implementing their own carried interest tax reforms.

The Global Context

The United States isn’t alone in grappling with carried interest taxation. The United Kingdom, for instance, taxes carried interest as capital gains but at higher rates than the U.S. Some European countries have moved toward treating at least a portion of carried interest as ordinary income.

The Bottom Line

The carried interest debate transcends simple tax policy—it reflects fundamental questions about fairness in our economic system. Should highly compensated investment professionals receive tax advantages unavailable to other workers? Does the current system appropriately reward risk-taking and investment, or does it simply preserve a significant tax benefit for an already privileged group?

As income inequality remains a central economic and political issue, carried interest continues to symbolize the complex intersection of tax policy, economic incentives, and social equity. Whether it represents a justified incentive for productive investment or an unfair loophole depends largely on one’s economic perspective—but understanding the mechanics and implications of carried interest is essential for any informed discussion about tax fairness in America.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute tax, legal, or financial advice. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, tax laws and policies are subject to change, and interpretations may vary. Readers should consult a qualified tax professional or legal advisor for personalized guidance regarding carried interest and related tax matters. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of any specific organization, institution, or government entity.