On July 4, 1850, President Zachary Taylor stood beneath the sweltering Washington sun, attending a celebration at the unfinished Washington Monument. He was a soldier-president, a war hero who had risen to the White House with no political background, propelled by his battlefield fame and plainspoken style. That day, he consumed a generous helping of cherries and iced milk. Five days later, he was dead.

What killed the 12th president of the United States? Officially, it was cholera morbus—a 19th-century term for what we might call severe food poisoning or acute gastroenteritis. But almost immediately, whispers of foul play began to circulate. Taylor, a Southern slaveholder who had dared to oppose the expansion of slavery into the western territories, had made enemies in high places. And now, he was suddenly gone.

The General Who Wouldn’t Bend

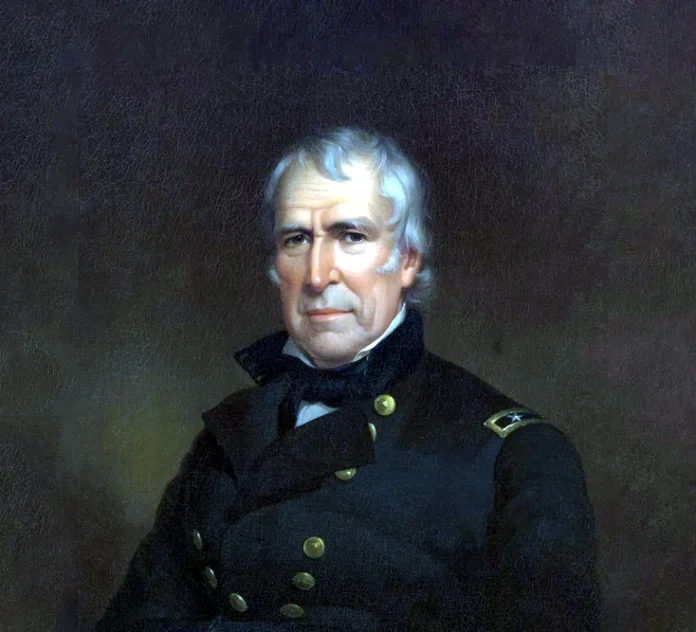

Taylor was not a typical politician. A career soldier known as “Old Rough and Ready,” he had earned his fame in the Mexican-American War, most notably at the Battle of Buena Vista. His plain clothes and gruff demeanor made him an appealing figure to a country weary of Washington insiders. But once in office, Taylor quickly proved he had ideas of his own.

Despite being a slaveholder himself, Taylor opposed the expansion of slavery into the lands acquired after the Mexican War. He supported immediate statehood for California and New Mexico as free states, bypassing the traditional territorial stage. To Southern firebrands, this was a betrayal. To Northern abolitionists, it was too little. Taylor, trying to preserve the Union, had managed to enrage both camps.

By the summer of 1850, tensions were boiling over. Texas was threatening military action over its territorial claims. Talk of secession was in the air. Taylor, never one to flinch, reportedly told advisers he would lead the army himself against any state that tried to break from the Union.

Then came the cherries and milk.

Death in the White House

After returning to the White House from the July 4 event, Taylor began to experience intense stomach pain. His symptoms worsened over the next few days: nausea, diarrhea, fever. White House doctors diagnosed him with cholera morbus and treated him with the era’s standard remedies: opium, quinine, and calomel (a mercury-based compound), along with bleeding and blistering. The treatments likely did more harm than good.

Taylor died at 10:35 p.m. on July 9, 1850. He was 65 years old. His death shocked the nation.

Vice President Millard Fillmore assumed the presidency. Within months, he signed the Compromise of 1850 into law—a series of measures Taylor had opposed. Among them was the notorious Fugitive Slave Act, which inflamed Northern resistance and moved the country closer to civil war.

A Whisper Campaign That Wouldn’t Die

Almost immediately, rumors began circulating: Zachary Taylor had been murdered. Southern extremists, it was said, had poisoned the president to clear the path for pro-slavery policies. Others pointed fingers at Catholics or at his political rivals. In 1881, former congressman and Lincoln assassination prosecutor John Bingham publicly accused Jefferson Davis of orchestrating Taylor’s death.

But the theory remained just that—a theory. There was no forensic evidence, no autopsy, no hard proof. Until a century later.

Digging Up the Past

In the late 1980s, Clara Rising, a historian and former University of Florida professor, began pushing for the president’s body to be exhumed. She believed the symptoms Taylor exhibited were more consistent with arsenic poisoning than cholera. With the consent of Taylor’s closest living descendant, the body was disinterred in 1991 from its tomb in Louisville, Kentucky.

Samples of Taylor’s hair and fingernails were sent to Oak Ridge National Laboratory, where scientists used neutron activation analysis to test for arsenic. The results showed that Taylor’s remains did not contain lethal levels of the element. He had not been poisoned—at least not by arsenic.

A Mystery That Still Lingers

If Taylor wasn’t poisoned, what killed him? Most historians now believe the culprit was contaminated food or drink—a common killer in 19th-century Washington, which was notorious for its poor sanitation. The milk may have been unpasteurized, the cherries washed in tainted water. Or perhaps it was the treatment that sealed his fate. As one medical review noted, “ipecac, calomel, and blistering” might have done more damage than the illness itself.

Still, some remain unconvinced. The test ruled out arsenic, but not every possible poison. And the political motive remains compelling. Zachary Taylor died just as he was taking a hard stand against slavery’s spread—a stance that could have reshaped the nation’s path to war.

In the end, the mystery of Zachary Taylor’s death lingers as a reminder of a nation on the brink. Whether felled by disease or design, the general who wouldn’t bend left behind a vacuum that changed American history. And over 170 years later, his last days continue to provoke questions no forensic test can fully answer.