The U.S. government orders the forced relocation and internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

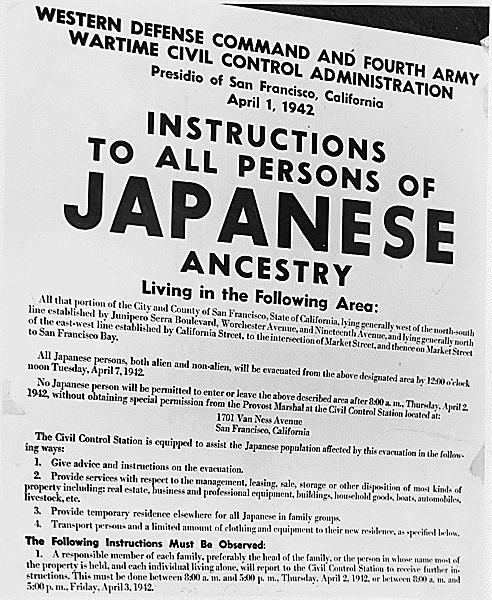

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the forced relocation and incarceration of over 120,000 Japanese Americans, many of whom were U.S. citizens. The order, justified as a wartime security measure, led to one of the most controversial civil rights violations in American history.

Background: Fear and Prejudice in Wartime America

In the wake of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, anti-Japanese sentiment surged across the United States. Fears of espionage and sabotage fueled public hysteria, particularly on the West Coast, where a significant Japanese American population resided. Despite a lack of evidence proving disloyalty, political and military leaders pressured Roosevelt to take action against those of Japanese ancestry. War Secretary Henry Stimson and General John L. DeWitt were among the most vocal advocates for internment, arguing that Japanese Americans posed a security threat simply due to their race.

The Order and Its Implementation

Executive Order 9066 gave military authorities the power to designate certain areas as exclusion zones and forcibly remove individuals deemed a threat. Although the order did not explicitly mention Japanese Americans, it was almost exclusively applied to them. By the spring of 1942, families were given just days to pack their belongings and were then transported to internment camps in remote areas such as Manzanar, Tule Lake, and Heart Mountain. These camps, surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards, housed entire communities under harsh conditions.

Impact and Consequences

The internment uprooted lives and caused immense suffering. Families lost homes, businesses, and personal belongings. Many Japanese Americans served in the U.S. military while their families were imprisoned, such as those in the highly decorated 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Despite legal challenges, including the landmark Korematsu v. United States (1944), the Supreme Court upheld the internment policy at the time.

After the war, internees were released, but most returned to shattered communities and financial ruin. It was not until 1988 that the U.S. government formally apologized through the Civil Liberties Act, offering reparations of $20,000 to each surviving victim.

Legacy and Reflection

Executive Order 9066 remains a stark reminder of how fear and prejudice can undermine civil liberties. Today, the internment of Japanese Americans is widely viewed as a grave injustice, studied in schools and commemorated in museums and historical sites. The event serves as a lesson on the dangers of racial profiling and government overreach during times of crisis.

Roosevelt’s decision continues to provoke debate about national security and civil rights, highlighting the importance of vigilance in protecting freedoms—even in wartime.